食と植

Food and Plants

料理も花も、“根っこ”をたどれば同じ植物。

そう思えたのは、2年前、ひとつの植物が身を守るための衣として、

命をつなぐための食として生かされていた、

かつての日本の暮らしと出合い直すことができたからだ。

私たちが一生をかけても経験から学びきることのできない知恵を、

過去に生きた人々は無言のうちに形として遺してくれている。

100年、200年と、地層のように重ねられてきた、

この地に生きるための工夫、その術が、今も私たちの足元にしっかりと刻まれている。

そう教えてくれたのは、茅葺き職人の相良育弥さんだった。

人が生きるために必要不可欠とされてきた「衣食住」。

「衣」のように「住」にも、過去からのたくさんのメッセージが眠っている。

私たちは、大きな時代の波にさらわれてしまいそうなこのメッセージを受け取り、

次の100年、200年へと、新たな層を重ねていくことができるだろうか。

野村友里・壱岐ゆかり

Cooking and flowers both come from plants at the “root” of it all.

We found our way to this conclusion two years ago when we rediscovered

a traditional Japanese way of life where a single plant turned into clothing

to protect the body as well as food to sustain life.

People that lived before us have taken troves of wisdom that couldn’t possibly

be gathered in a single lifetime, and quietly passed them onto us in tangible formats.

Ideas and skills for living on this land have been accumulated like

geological layers for 100 years, 200 years, and are ingrained in our modern lives.

The person who taught us this was our friend and thatcher, Ikuya Sagara.

“Clothing, Food, Shelter” are the key components that make our livelihoods.

As with “clothing”, there are so many messages from the past hidden within

the realm of “shelter.” So the question is, can we uncover those messages

before they are swept away by the tides of time and are we capable of creating

new layers of life to be passed on into the next 100 and 200 years?

Yuri Nomura ⁄ Yukari Iki

安心できる

居場所どこにある?

Where is our place of peace?

大麻布との出合いから2年がたったころ、

思いがけず、私たちは店を構えて10年を過ごした神宮前を立ち退くことになり、

新しい居場所を探さなければならなくなった。

この2年で、またたく間に都会と田舎の距離は埋まり、

通信環境さえあれば、どこにでも暮らせるようになった。

どこにでも暮らせる自由を手に入れたはずなのに、どこか不安なのはなぜだろう?

最新のセキュリティ、最新の耐震性能があれば、安心と言えるのかな?

ほんとうの安心、ほんとうの居場所は、どこにあるんだろう?

“衣”から“住”へ。

私たちの新たな居場所探しとともに、“住”の学びが始まった。

Two years after our discovery of Taima-fu, we found ourselves unexpectedly having to make the decision to give up our store in Jingumae, our home of 10 years, and finding a new place to set down our roots.

In those two years, social circumstances had brought cities and countrysides much closer and people could live wherever they pleased, as long as they were connected online.

However, despite having gained the freedom to live anywhere, there was an unshakable sense of uncertainty. Could we really say we feel secure as long as we lived in an earthquake resistant building with the latest security?

Where could we find a true sense of peace and a place of belonging?

We shifted from “clothing” to “shelter” and set out to find a new home.

Along with it, our journey in learning about “shelter” began.

何度でも直して使う、

何度だってやり直せる

Fix, use, repeat

どんな素材で、どうつくられているんだろう?

現代の住宅は、想像することも難しい。

だけど、かつての民家は、自然素材だけ。

とてもシンプルにできていた。

茅葺き屋根、土壁、ふすまや障子……日本の住居に息づいていた職人たちの仕事。

伝統技法を今の感性で受け継ぐ職人たちとの出会いから、“直せる”暮らしが見えてきた。

土に還る素材によって人の手でつくられたものは、

何度でも直して、何世代にもわたって使い続けることができる。

何度でも直しながら、“良化”していく。

服だって、家だって、人だって。

What is this house made from and how was it made?

It’s hard to imagine with the modern home.

Old homes were made entirely from natural ingredients.

Things were simple back then.

Thatched roofs, earthen walls, paper screens and doors…

the work of craftsmen breathed life into Japanese homes.

We met craftsmen who pass on traditional techniques

with a modern twist and through them, we discovered a “fixable” way of life.

Things made by hand from natural materials can be fixed

however many times and be used across generations.

The more it’s fixed, the “better” it gets.

For clothes, for homes, and even people.

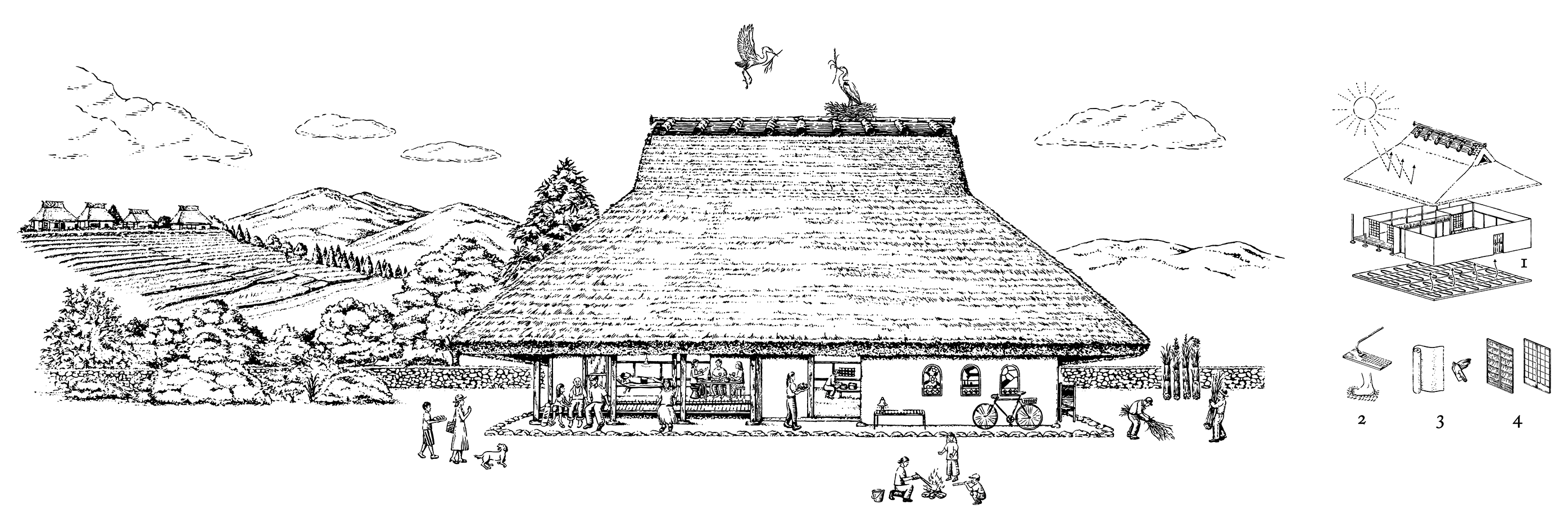

相良育弥 茅葺き職人

Ikuya Sagara: Thatcher

本展のきっかけとなった相良育弥さんとの出会い。日本の「住」といえば、田んぼと茅葺き屋根の民家が並ぶ田園風景が思い浮かびます。阪神淡路大震災をきっかけに、何があっても生き抜いてゆける知恵を学ぶために茅葺き職人となった相良さんの「日本の暮らしには稲が欠かせない」というお話から、本展の構想が拡がっていきました。

Our encounter with Ikuya Sagara was the inspiration that led to this exhibition. A “home” in Japan instantly brings to mind an idyllic rural scenery with rice paddies and rows of thatched-roof homes. Sagara-san became a thatcher after the Great Hanshin earthquake in pursuit of wisdom that would allow him to survive any circumstance. The idea for this exhibition was born through our conversations on the importance of rice is in the Japanese way of life.

大橋和彰 左官職人

Kazuaki Ohashi: Plasterer

若いころから、貨幣経済への違和感や世の中の矛盾に対して問題意識があったという大橋和彰さん。世界中を旅するうちに、「土や石のようなどこにでもある素材で、暮らしをゼロからつくり上げる技術を身につけたい」と考えるようになり、左官の道へ。伝統技術を軸に、素材や感性や知識を生かして「誰かの空間を快適にすること」を信条とされています。

From a young age, Ohashi-san says he questioned monetary economies and was aware of the contradictions that exist in our society. As he traveled the world, his desire to learn how to use ordinary materials like earth and rocks to build a lifestyle from scratch grew and eventually led him down the path of becoming a plasterer. Based in traditional techniques, Ohashi-san’s concept is to leverage materials, inspiration, and knowledge in “creating a place of comfort for others.”

ハタノワタル 和紙職人

Hatano Wataru:

Japanese paper craftsman

障子、提灯、傘、衣など、かつては生活の中で多用されてきた和紙を、現代の生活に生かせるものとして、美しくモダンな形に落とし込むハタノワタルさん。原材料の楮 を自ら栽培し、その処理から手漉きまでほぼ手作業で行っています。アーティストとしても知られていますが、実は個人の「住まい」に関わる仕事がいちばんうれしいのだとか。なぜなら「暮らしのなかで使ってこそ、和紙の本当のよさがわかる」から。

Wataru Hatano takes Japanese paper, a material historically found in various parts of our lives from paper doors and lanterns to umbrellas and clothes, and gives it a beautiful twist to suit our modern way of living. Hatano-san grows his own Kozo (paper mulberry), the ingredient to paper, and carries out the entire process by hand from the processing of the Kozo to the making of the paper. He is well known as an artist but says that working in private “homes” brings him the greatest joy because “the true beauty of Japanese paper is revealed through daily use.”

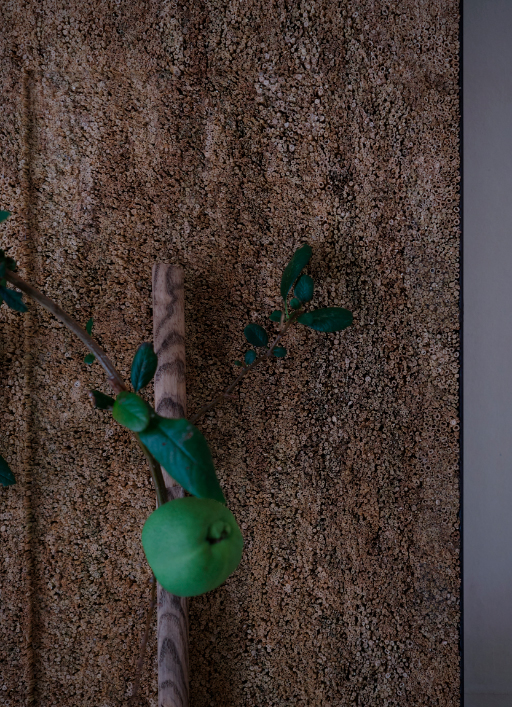

稲という植物を、

使いつくす

Using the whole rice plant

日本という国が生まれた、はじまりのはじまりのころ。

私たちの祖先は、この小さな島国を

「みずみずしい稲が育ち、豊かな収穫がつづく、すばらしい国」と呼び、

山や森、石や岩、木の枝一本まで、

あらゆる自然物に神さまが宿っていると信じていた。

稲は、この国で長く暮らしていくために、神さまが最初に授けてくれたもの。

この大事な稲を、お米として食べるだけでなく、

工夫をこらして最後の最後まで使いつくした。

振り返ると、“住”のいたるところに稲があった。

“衣”に欠かせなかった大麻、“住”に欠かせなかった稲。

私たちの足もとにあった二大植物。

Way back when, at the dawning of this country called Japan.

Our ancestors called this small island country,

“a beautiful land where lush rice grows and plentiful harvests continue.”

The people believed that God lived in every corner of nature from the mountains

to the forests, rocks and boulders, trees, and down to a single branch.

Rice was the first thing that God

bestowed upon the people to sustain themselves.

Not only did they consume this precious rice as food

but they thought of ways to use it to the very end.

Looking back, rice was found everywhere inside the home.

Rice was integral to “homes” as hemp was to “clothing”.

These were the two plants that we lived by.

“育てる”は“輝く”

Grow=Glow

青々とした緑色から、黄金色に輝く稲のじゅうたんが、

日本中に敷き詰められていた。

村中みんなで稲を育て、食べること、住まうこと、さまざまに使いつくし、

やがては土へと還していく。

木々や虫や動物、すべての生きものが、関わり合いながら次の種をつなぎ、

土へと還っていく連環の大きな輪の中に、人の営みもあった。

稲があれば、安心だった。

安心を得るための稲だった。

育てることが、もっともっと輝いていた。

Everywhere you went, Japan used to be an endless carpet of rice that turned from lush green to golden glimmer as the season changed.

Village people grew rice together as food, for homes, and other purposes until eventually returning it to the soil.

Trees, bugs, animals, and other living creatures played their part in passing on its seed and people’s lives were also a part of this one great cycle that returns to the earth.

There was a sense of peace as long as there was rice.

Rice was what provided us with security.

This was a time when growing had more glow.

「綯」Video 09’46”

日本最古の茅葺き民家〈箱木家住宅〉

Japan’s oldest thatched roof home

〈Hakogi Residence〉

相良育弥さんの茅葺き修復作業

Ikuya Sagara’s repairing of a thatched roof

大島農園の田植え

Rice planting at Oshima Farm

上甲 清さんのしめ飾りづくり

Kiyoshi Joko’s Shimenawa making

陶芸家の十場天伸・あすかさん一家が

暮らす茅葺き民家

Thatched roof home of ceramic artists

Tenshin & Asuka Juba and family

大島農園(栃木県)

Oshima Farm

(Tochigi Prefecture)

以前は〈the little shop of flowers〉のスタッフだった大島和行さん。数年前に実家のある栃木へ戻り、農薬・科学肥料を一切使用せずに米づくりをはじめました。昨年、近隣の水源近くにある、担い手のいなくなった6町もの田んぼを「集落の景色を守りたい」という一心で引き受けようと一大決心。草取りから田植え、収穫まですべてを夫婦二人で行っています。

Kazuyuki Oshima is a former staff of 〈the little shop of flowers〉. Several years ago, he returned to his hometown in Tochigi Prefecture where he started growing rice using absolutely zero agrichemicals / chemical fertilizer. Last year, in a mission to, “Preserve the village’s scenery”, Kazuyuki made a major decision to take on 14.5 acres of rice paddy near a local water source which would have been left abandoned otherwise. The entire rice growing process from weeding, planting, and harvest are tended to by Kazuyuki and his wife, just the two of them.

上甲 清(愛媛県)

Kiyoshi Joko

(Ehime Prefecture)

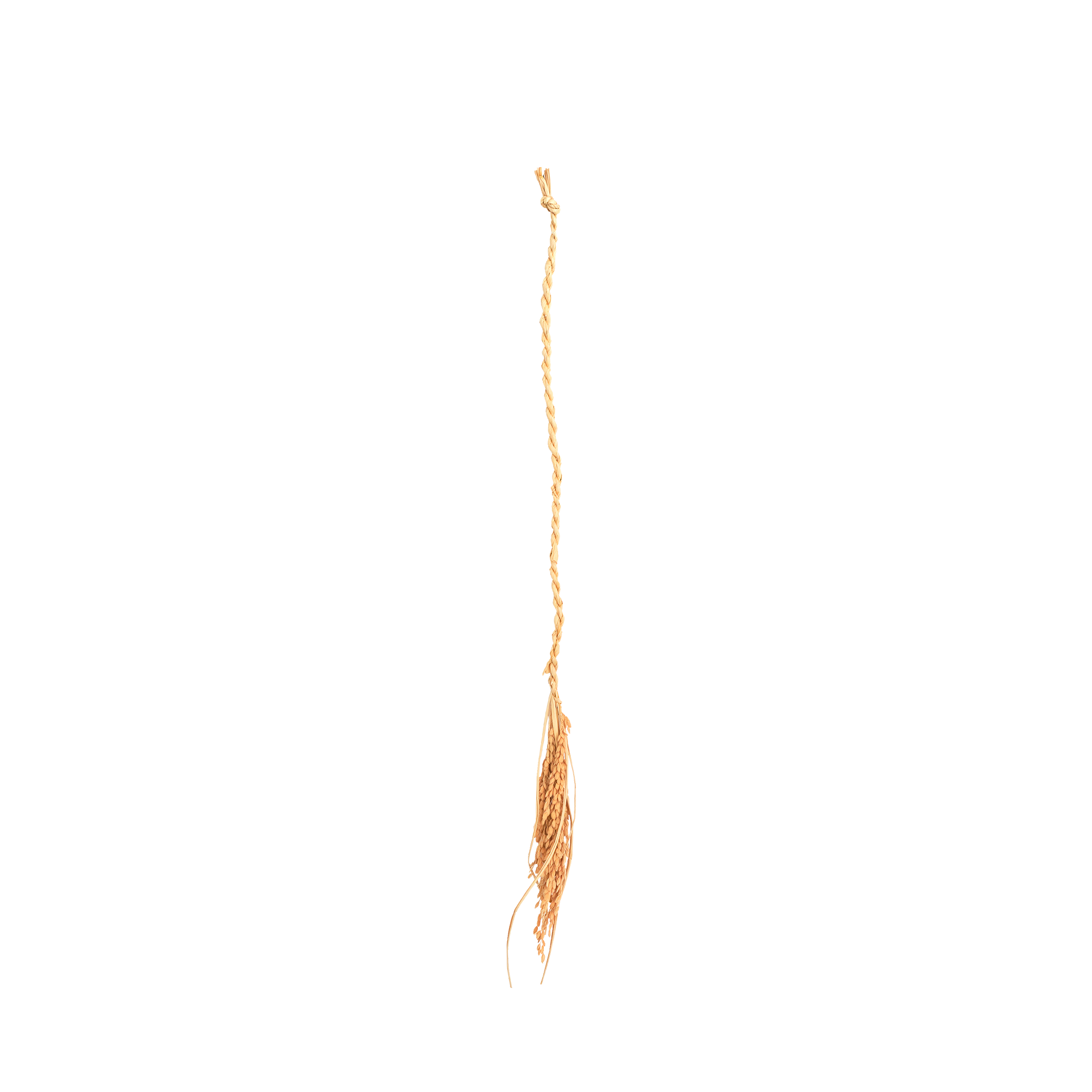

壱岐が、ある⺠藝品店で出合ったしめ縄があまりにもうつくしくて、店主に紹介してもらったという農家であり、しめ縄職人の上甲清さん。「山と、そこから流れるきれいな水と、わらぼっちが佇む田んぼがある、この土地にしかない景色を残したい」。そんな思いから、愛媛県の米どころである西予市で、自ら育てた稲わらでしめ飾りをつくり続けています。

One day, Iki came across a Shimenawa in a craft shop that was so beautiful that she asked the shop owner to be introduced to its maker, who was farmer and Shimenawa craftsman Kiyoshi Joko. “There is the mountain, the clear water that runs from it, and the rice paddy where the haystacks stand. I want to preserve this unique scenery of my land.” This emotion drives him to continue making Shimekazari from the straw that he grows himself in Seiyo, a major rice-producing region of Ehime prefecture.

井上吉夫さんの稲わら

Straw by Yoshio Inoue

「かかりつけ医」が「頼れる身近なお医者さん」を意味するように、「つくり手の顔が見える生産直売」をモットーとして、「かかりつけ米農家」を屋号に掲げている井上吉夫さん。高齢化によって休耕田が目立ち始めた村にて稲を育て、直売を始めて33年目。本展のために、収穫したばかりの稲330束を提供してくださいました。

Just like a “home doctor” refers to a nearby doctor that can be counted on, Yoshio Inoue farms under the name of a “Kakaritsuke Kome Nouka (home rice farmer)” based on the motto of, “production and direct sales of rice that people can put a face to.” It’s been 33 years since he started direct sales of rice grown in a village where more and more rice paddies were becoming abandoned due to an aging society. Yoshio-san generously provided 330 bundles of freshly harvested rice especially for this exhibition.

700年“生きてきた”家

Homes that have “lived” 700 years

日本で一番古いという、築700年の茅葺き民家を訪ねた。

動物たちの巣のように、土と木と草というシンプルな材料だけでつくられ、

数百年の時を生きてきた家。

大きな屋根の下に入ると、なんだかほっとした。

大きな木の下で、包まれているようだった。

足裏に感じる木の床はうっすらと波打っていて心地よく、

部屋じゅうをいい風が通っていた。

未来に残したい家、何世代にもつないでいける暮らしの姿が、

うっすらと脳裏に浮かんできた。

We visited a 700-year-old thatched roof home said to be the oldest existing home in Japan. This home, that has lived for centuries, was like an animal’s nest made from simple materials like mud, trees, and grass.

We felt a sense of relief upon stepping under the big roof.

Like being embraced by a majestic tree.

The chiseled wooden floor was soothing under our feet and a gentle breeze flowed through the rooms.

Images of a home to save for the future and that of a lifestyle that connects generations, started taking shape in our minds.

日本でみんなが麻布の服を着て暮らしていたころ、

お母さんが家族には内緒で、家計を支えるために

麻糸を紡ぐ内職をしてコツコツと貯めていた

お金のことを「綜麻繰り(へそくり)」と呼んでいました。

今に生きる私たちが、

今よりも“よりよい”未来の世界を思い描けたなら、

そこへ近づいていけるものづくりを

生活に取り入れていきたい。

コツコツと、ちょっとずつでもいい、

つくり手の思いに触れて「いいね」と

応援したくなるものたちを、

身の回りに増やしていきたい。

それを、私たちは“平和のへそくり”と

呼ぶことにしました。

その土地土地に「いい根」を張り、

循環するものづくり。日本固有のうつくしさへの

眼差しを持ったつくり手たちの品々を、

ここに集めました。

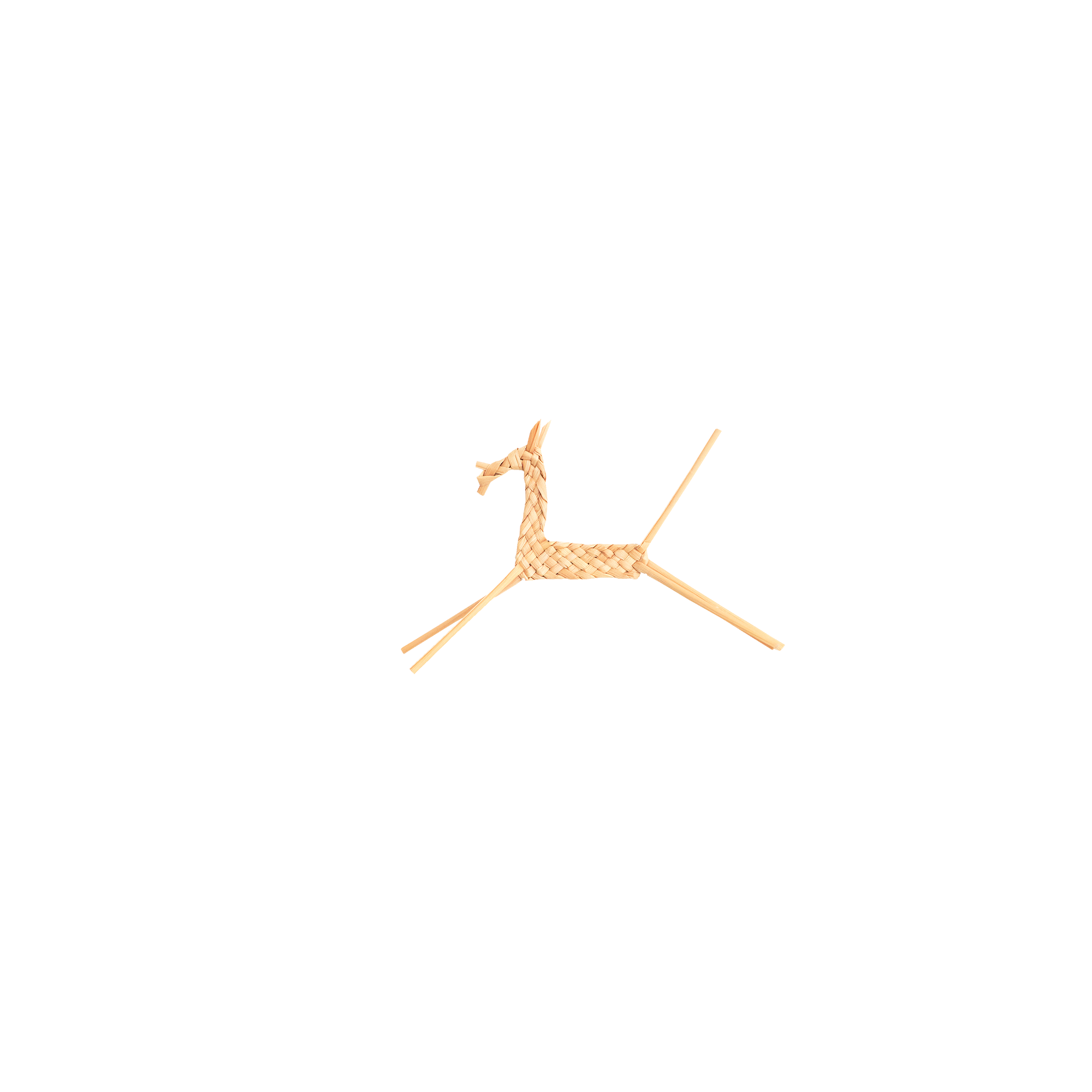

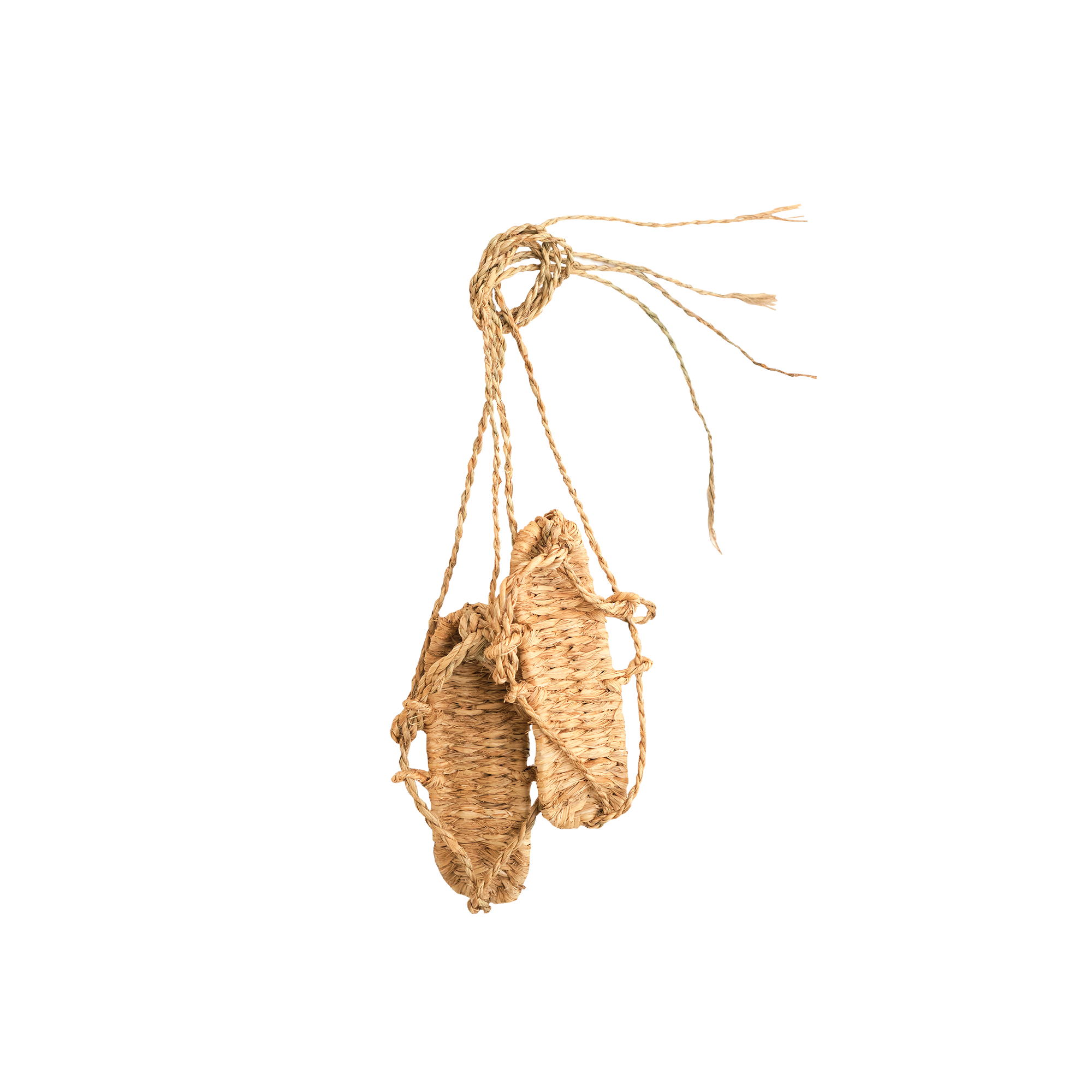

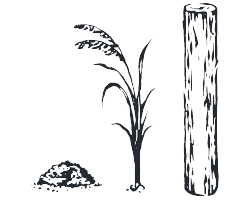

稲わらの日用品

Daily Items From Straw

昔は秋に稲刈りが終わると、稲わらで米を出荷するための俵を編み、農閑期となる冬には縄を綯い、夜なべでわら仕事を行いました。稲わらは、木槌で打つとやわらかわらじみのく丈夫になります。これで、草鞋、雪靴、蓑のほか、かご鍋敷き鍋つかみ、唐辛子や柿を干すための紐、納豆やつと卵などを包む苞など、多彩な日用品がつくられました。

Once rice was harvested in the fall, people used the straw to weave bales for shipping the rice. During the winter off season, farmers worked through the night weaving straw ropes. They pounded the straw with a wooden hammer to make it softer and more durable. With this, they made sandals, snow boots, and raincoats, and a myriad of other items like baskets, pot mats, pot holders, string for hanging red peppers and persimmons, and wrappers for wrapping "natto (fermented soy bean)" and eggs.

稲わらの日用品

Daily Items From Straw

昔は秋に稲刈りが終わると、稲わらで米を出荷するための俵を編み、農閑期となる冬には縄を綯い、夜なべでわら仕事を行いました。稲わらは、木槌で打つとやわらかわらじみのく丈夫になります。これで、草鞋、雪靴、蓑のほか、かご鍋敷き鍋つかみ、唐辛子や柿を干すための紐、納豆やつと卵などを包む苞など、多彩な日用品がつくられました。

Once rice was harvested in the fall, people used the straw to weave bales for shipping the rice. During the winter off season, farmers worked through the night weaving straw ropes. They pounded the straw with a wooden hammer to make it softer and more durable. With this, they made sandals, snow boots, and raincoats, and a myriad of other items like baskets, pot mats, pot holders, string for hanging red peppers and persimmons, and wrappers for wrapping "natto (fermented soy bean)" and eggs.

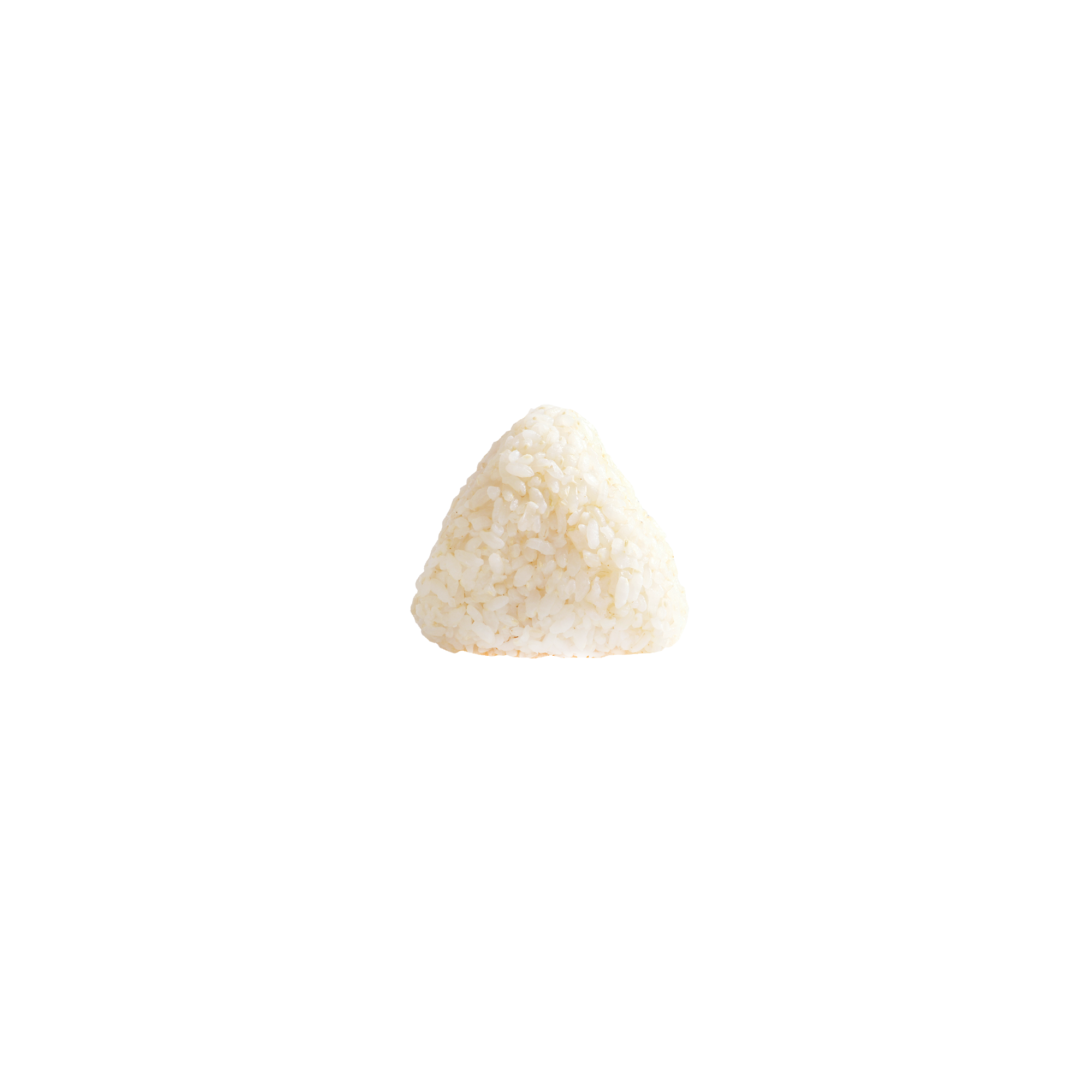

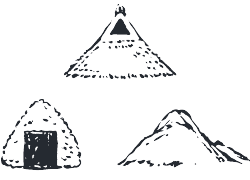

三角おむすび

Triangle Rice Balls

農耕文化の始まりとともに、人々は稲作において不可欠な水の源である山に対して神聖感を抱くようになり、やがて神体山として崇めるようになりました。 一説によると、山の形を模した三角形のおむすびをお供えしてから口にすることで、神様の力をいただけると信じていたといわれています。

The birth of farming culture led people to regard mountains, the source of the water that is imperative in rice cultivation, as something sacred. Soon, they started worshiping these sacred mountains. According to one theory, people believed that they would be able to receive God's help by offering mountain-shaped rice balls to the gods and then eating them.

稲わらの日用品

Daily Items From Straw

昔は秋に稲刈りが終わると、稲わらで米を出荷するための俵を編み、農閑期となる冬には縄を綯い、夜なべでわら仕事を行いました。稲わらは、木槌で打つとやわらかわらじみのく丈夫になります。これで、草鞋、雪靴、蓑のほか、かご鍋敷き鍋つかみ、唐辛子や柿を干すための紐、納豆やつと卵などを包む苞など、多彩な日用品がつくられました。

Once rice was harvested in the fall, people used the straw to weave bales for shipping the rice. During the winter off season, farmers worked through the night weaving straw ropes. They pounded the straw with a wooden hammer to make it softer and more durable. With this, they made sandals, snow boots, and raincoats, and a myriad of other items like baskets, pot mats, pot holders, string for hanging red peppers and persimmons, and wrappers for wrapping "natto (fermented soy bean)" and eggs.

稲わらの日用品

Daily Items From Straw

昔は秋に稲刈りが終わると、稲わらで米を出荷するための俵を編み、農閑期となる冬には縄を綯い、夜なべでわら仕事を行いました。稲わらは、木槌で打つとやわらかわらじみのく丈夫になります。これで、草鞋、雪靴、蓑のほか、かご鍋敷き鍋つかみ、唐辛子や柿を干すための紐、納豆やつと卵などを包む苞など、多彩な日用品がつくられました。

Once rice was harvested in the fall, people used the straw to weave bales for shipping the rice. During the winter off season, farmers worked through the night weaving straw ropes. They pounded the straw with a wooden hammer to make it softer and more durable. With this, they made sandals, snow boots, and raincoats, and a myriad of other items like baskets, pot mats, pot holders, string for hanging red peppers and persimmons, and wrappers for wrapping "natto (fermented soy bean)" and eggs.

稲わらの日用品

Daily Items From Straw

昔は秋に稲刈りが終わると、稲わらで米を出荷するための俵を編み、農閑期となる冬には縄を綯い、夜なべでわら仕事を行いました。稲わらは、木槌で打つとやわらかわらじみのく丈夫になります。これで、草鞋、雪靴、蓑のほか、かご鍋敷き鍋つかみ、唐辛子や柿を干すための紐、納豆やつと卵などを包む苞など、多彩な日用品がつくられました。

Once rice was harvested in the fall, people used the straw to weave bales for shipping the rice. During the winter off season, farmers worked through the night weaving straw ropes. They pounded the straw with a wooden hammer to make it softer and more durable. With this, they made sandals, snow boots, and raincoats, and a myriad of other items like baskets, pot mats, pot holders, string for hanging red peppers and persimmons, and wrappers for wrapping "natto (fermented soy bean)" and eggs.

稲わらの日用品

Daily Items From Straw

昔は秋に稲刈りが終わると、稲わらで米を出荷するための俵を編み、農閑期となる冬には縄を綯い、夜なべでわら仕事を行いました。稲わらは、木槌で打つとやわらかわらじみのく丈夫になります。これで、草鞋、雪靴、蓑のほか、かご鍋敷き鍋つかみ、唐辛子や柿を干すための紐、納豆やつと卵などを包む苞など、多彩な日用品がつくられました。

Once rice was harvested in the fall, people used the straw to weave bales for shipping the rice. During the winter off season, farmers worked through the night weaving straw ropes. They pounded the straw with a wooden hammer to make it softer and more durable. With this, they made sandals, snow boots, and raincoats, and a myriad of other items like baskets, pot mats, pot holders, string for hanging red peppers and persimmons, and wrappers for wrapping "natto (fermented soy bean)" and eggs.

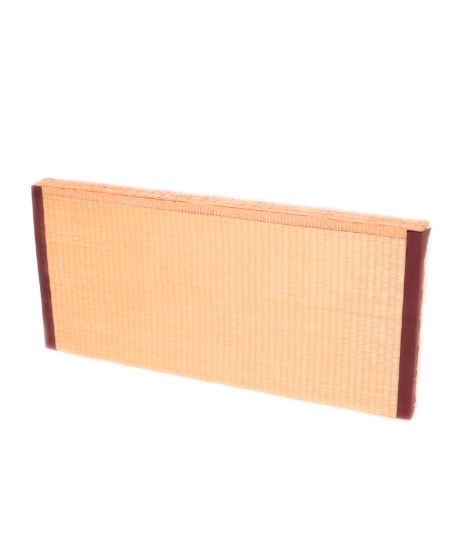

畳

Tatami

畳の前身は、わらで編んだ敷物である筵。特別なときに 筵をたたみ重ねたことから畳が生まれました。畳表はたたみどこ イグサですが、その中身は稲わらを何重にも重ねた畳床。建材でつくられた畳床が主流である現在も、本畳といえば稲わら畳床を用いたもの。適度な硬さとやわらかさ、調湿作用、断熱効果が素晴らしく、チリやホコリを吸引するので空気清浄効果もあります。

Tatami can be traced back to a straw mat called "mushiro." People layered "mushiro" on top of one another for special occasions and this eventually led to the creation of tatami. The very outer layer of a tatami is made using rush grass but the core consists of layers upon layers of straw. Although most tatami made today use other materials for its core, a traditional tatami with a straw core offers a good balance of firmness and softness, controls humidity, offers outstanding insulation, and also draws in dust to purify the air.

しめ飾り

New Year's Decorations

しめ飾りの原型は、神社で見られるしめ縄。 その年の稲 でできた新しいわらを使って、 一年の無事を感謝し、新し い春を迎える気持ちを込めてつくります。 うるち米よりも ち米、品種改良された現代種より古代品種のほうが、 わら が長くしなやかでつくりやすいと言われています。減反 政策によって、 しめ飾り用の稲を育てる農家が増えたこと もあり、地方や家々によって多様な意匠や技法があります。

Shime-kazari, or New Year's decorations, originally started from "shime-nowa" or sacred ropes found in Shrines. Fresh straw from the year's rice harvest is used to give thanks for a safe year while preparing for the new spring ahead. It is said that the straw of sticky rice outshines ordinary rice, and that ancient varieties, more than modern breeds of rice, provide longer, pliable and easier-to-use straw The enactment of the rice acreage reduction policy led to increased production of rice straw specifically for shime-kazari, and this, in part led to diversification of local designs and techniques.

酒

Sake

古来、自然や神に対して捧げる供物は、その土地でとれる最上のものとされてきました。稲作で栄えてきた日本では、米からつくられた酒は特に価値のあるもの。 豊 おみき作や無病息災を祈って神に捧げる酒を 「御神酒」といい、そのお酒を人が飲むことでご利益をいただきます。 酒は 神と人を結びつける神聖なものであり、現在も結婚式や お正月といった儀式に欠かせません。

Since ancient times, it was agreed that offerings to nature and God were to be those of the highest grade produced on the land. Japan prospered through rice cultivation and hence, sake produced from rice was of particularly high value. Sake offered to God when praying for plentiful harvest and good health is called "omiki" and drinking this sake brings good fortune. Sake is sacred in that it connects people with God and is always present, even today, in ceremonies such as weddings and New Year's festivals.

わら半神

Straw Paper

正倉院文書には、稲わらの繊維を原料とした和紙「わら 「葉紙」の記述がありますが、私たちに馴染みがあるのは ざら紙とも呼ばれていた「わら半紙」。木綿のウエスとわらを原料に、明治時代初期に生産が始まりましたが、実は数年後の1889年頃には、わらは木材パルプに切り 替えられていました。

Documents from Shoso-in Treasure House include a passage regarding "wara-yoshi", a Japanese paper made from rice straw fibers. Today, we are more familiar with "wara-banshi", sometimes also called "zara-shi." Made from cotton rags and straw, production of "ward- yoshi" began in the early Meiji Era until it was replaced no sooner by wood pulp in 1889.

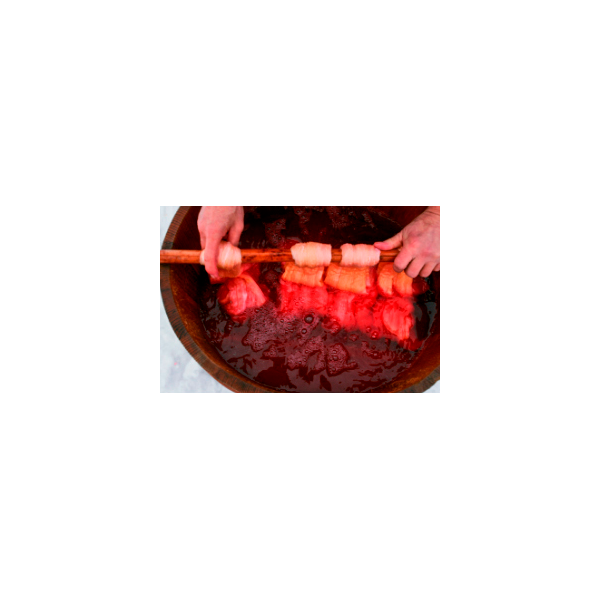

わら灰と染色

Straw Ash and Dyeing

稲わらを焼いてつくったわら灰は、そのアルカリ成分を 生かして、糸や布の精錬や染色にも活用されていました。 わら灰に熱湯を加えてから沈殿させると、 その上澄み液 が灰汁と呼ばれるアルカリ性の液体になります。 これが 染色に欠かせない助剤となり、 特に紅花のうつくしい赤 の色素を抽出する上では最も重要です。

Alkali that is present in straw ashes made from burnt straw was used for scouring and dyeing threads and cloth. When straw ash is mixed with hot water and left to settle, the clear liquid on top turns into an alkaline liquid called lye. Lye is an auxiliary that is pivotal in extracting the beautiful red color when dyeing with safflower.

陶器 (釉薬)

Pottery (Glaze)

昔の暮らしは半農半工。 農閑期にわら細工や竹細工、 陶 芸などの工芸を行い収入を得ていました。 このため陶芸 と稲作のかかわりは深く、 稲にはプラントオパールと呼ば れるガラス質が多く含まれているため釉薬として用いられ、 焼成したあとに出たわら灰は土壌改良剤として田畑に撒 くなど、稲を余すことなく使い切り循環させていました。

Traditionally, people divided their living throughout the year between farming and craft making. During off season, money was earned through the production of straw crafts, bamboo crafts, and pottery. Pottery and rice cultivation are closely connected by an active silica called "plant opal” contained in the straw, that is used as pottery glaze. Furthermore, the remnant straw ashes after firing pottery were scattered in rice paddies and fields for soil amendment, which meant that straw was literally used to the "last straw."

土壁

Earthen Walls

温度や湿度を調整し、 防音効果もある土壁は、 土と すさ 水、 そして稲わらを細かく切ったわらからできていま す。 土に水とわらを混ぜて寝かせると、 わらが発酵して 分解され、糊のような成分が溶け出します。 その粘り気 が、繊維状になったわらと土をつないで壁に強度を持たせ、 作業性を向上させ、 ひびわれを防いでくれます。

Earthen walls adjust temperature and humidity while also offering soundproofing qualities. These walls are made with soil, water, and finely chopped straw. When the materials are mixed and left to soak, the straw starts fermenting in the process and breaks down into fibers that release a component that is similar to glue. This viscosity binds the soil with the straw fibers. This not only makes the wall stronger but it improves ease of application while also preventing cracking of the wall.

山があって、田んぼがあって、

風景が育まれていく

Mountains and rice paddies create the scenery

たっぷりの水とふかふかの土に育まれた森、山、田畑。自然環境にとてもめぐまれていたかつての日本。生命力あふれる植物たちに囲まれた、私たちの暮らしの原風景。そこから生まれた日本の個性。

Forests, mountains, and rice paddies are nurtured by bountiful water and soft soil. Japan in the past was infinitely blessed in its natural environment. Our lifestyles were surrounded by thriving plants and that is where Japan’s identity was born.

山、屋根、おむすび……

ぜんぶ三角だ!

Mountains, roofs and rice balls are all triangles!

三角の山々に抱かれた、三角屋根の家並み。農耕に不可欠な水の恵みは山からもたらされることから、古来、田植えの時季には山の神さまが降りてきて、収穫を終えると山へ帰っていくと信じられていた。三角のおむすびも、もとは山の神さまにお供えするため、山に見立てた形に握ったのがはじまりとも言われている。

Homes with triangular roofs, are surrounded by triangle mountains. The blessing of water crucial in agriculture comes from the mountains, which is why in ancient times, people used to believe that the gods of the mountains would come down to the rice paddies during planting season and go back up once harvest was complete. Rice balls shaped in a triangle to look like a mountain were said to have been first made as offerings to those gods.

素材は、土と木と草、以上。

やがては土に還る家

Simple ingredients: soil, tree, grass. A home that returns to soil

茅葺き民家に使われる素材は、身のまわりにある土と植物だけ。鳥たちがつくる巣と同じ。使われなくなったとしても、やがては土に還っていく。

Materials used to build a thatched roof home consisted only of the soil and plants around us. Just like what birds use for their nests. Even if vacated, it eventually returns to soil.

家っていうか、ほとんど屋根!

More roof than house!

日本の民家の元祖は、竪穴式住居。土に穴を掘って屋根をかぶせただけの“巣”そのものだった。時代とともに家族単位で生活するようになり、単なる寝床だった“巣”から“家”へと進化する過程で屋根が地上へ持ち上げられていった。

The originator of Japanese homes was the pit-dwelling, which was literally a “nest” made from a hole in the ground with a roof on top. As people started living in family units, dwellings evolved from a “nest” into a “home”, during which process the roof was raised above ground.

葺き替えのサイクルは?

How often to re-thatch?

茅葺き屋根は、20〜30年ごとに葺き替える。その間、コツコツと身近にある茅(稲やすすきなどのイネ科植物)を貯めていく。今では、素材調達が難しくなり、屋根用に栽培されているんだそう。

Thatched roofs are re-thatched every 20-30 years. During that time, people saved straw (gramineous plants such as rice and silver grass) bit by bit. Today, straw is grown specifically for thatched roofs due to the difficulty in procuring them on a daily basis.

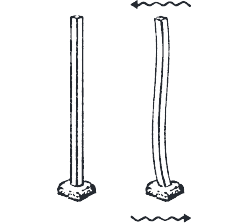

力を“いなす”知恵

Wisdom to “deflect” force

茅葺き屋根は、土台に噛ませて重しのように“のっている”だけ。現代建築はガチガチに固めようとするけれど、日本古来の建築は度重なる災害の経験から、固めない技法を編みだした。固めずに、“いなす”(力を逃す)。大きく揺れても土壁が崩れるだけで、屋根と柱はしっかり残る。崩れた土壁だけを直せばいい。

Thatched roofs basically “sit” like a weight upon its foundation. Contrary to modern architecture that reinforces, traditional Japanese architecture, having learnt from many past disasters, came up with methods that do the opposite. They “deflect (release energy)” instead of reinforcing. In the event of a large quake, the mud walls crumble but the roof and pillars remain. The only thing that needs fixing is the wall.

「弱い」じゃなく「強い」巨大地震でも

倒壊しなかった!?

“Strong” not “weak.” Withstands even huge earthquakes!?

災害の多い国ニッポンで、何千年と培われてきた知恵の結晶が、茅葺き民家だった。マグニチュード7.3を記録した阪神淡路大震災でも、震源地の兵庫県にある築数百年の茅葺き民家は、ほとんど倒壊しなかった。

Japan is a country of natural disasters and thatched roofs are the culmination of thousands of years of wisdom gained throughout. Even at the Great Hanshin earthquake which recorded a magnitude of 7.3, hardly any of the centuries-old thatched roof homes in Hyogo, the epicenter, collapsed.

三世代と斜め社会

Three generations and a diagonal society

親と子は反発しあっても、一世代挟むと余白が生まれる。家族や同世代といった縦と横の関係だけでなく、世代を超えて斜めに混ざり合う関係が村社会を強くした。今は失われていて、未来に必要なこと。

A parent and child may collide but having one generation cushioned in between creates space to breath. Villages were made stronger because in addition to a vertical and horizontal society of families and their generations, there was a diagonal relationship where people interacted with one another beyond bloodline and generations. It’s something we don’t have now but need for the future.

“グレー”な日本人は、

「縁側」に育まれた

“Grey” Japanese were born on “engawa(porches)”

真正面に向き合い白黒つける話し合いより、横に並んで景色を眺めながらのほうが言いづらいこともやんわりと口にできる。縁側は、村社会で日常的に起こる小さな問題を、大きくなる前に解決させる装置でもあった。

One can sit face to face and decide on black or white but it’s possible to have uncomfortable conversations in a peaceful way when you talk sitting shoulder to shoulder while gazing out at the scenery. Engawa (porches) was a tool that helped resolve trivial issues that occurred daily in villages before they got out of hand.

とても涼しくて、とても静か

So cool, so tranquil

調湿効果のある茅葺き屋根は、結露を起こしにくくカビの発生や木の傷みが少ないため、結果として建物が長持ちする。室内が木の下にいるかのようにシンと静かなのは、吸音性があるから。

Thatched roofs can control humidity, thereby preventing condensation and mold, which ultimately protects the wood and allows the building to last. The tranquility like standing under a tree, is due to the roof’s ability to absorb sound.

燃えやすいから、火を学ぶ

Flammability as a lesson in fire

茅葺き屋根の唯一とも言える弱点は、燃えやすいこと。だからこそ、昔は子どもが親から学ぶ大事な作法に「火の扱いかた」があった。知らないから、不安になる。素材を知り、構造を知り、弱点を知恵にする。

One of the very few weaknesses of a thatched roof is its flammability. That is why “handling fire” was one of the most important lessons that children learned from grownups. Uncertainty stems from lack of knowledge. Weaknesses could transform into wisdom by knowing with what and how something is made.

稲一本あれば、腕一本あれば、

仲間たちがいれば

What a single stalk of rice, a single arm, and good company can do

衣食住のすべてが手仕事だった時代、人は集まらないと生きてはいけなかった。「村」とは、「群れ(ムレ)」から生まれた言葉。安心を与えてくれるのは屋根だけじゃない、群れの支え合いだった。個人主義が尊重され、安心安全も個人がお金で買うしかなくなった戦後の日本。だけど最後の最後には、稲と仲間たちさえいれば、きっとなんとかなる。

Back when clothing, food, and housing were all made by hand, one could not live were it not for the help of many others. The word “mura (village)” was derived from “mure (crowds.)” Roofs provided safety but so did the support from the community. Post-war Japan turned into a society where individualism was respected and safety and security could only be bought. But, at the very end of it all, we could probably survive as long as we have rice and friends.

冬の寒さは、床暖房で解決

Solve winter chills with underfloor heating

夏の茅葺き民家は、エアコンいらず。日中、太陽から受けた熱をうまく逃してくれるので、夜には涼しく快適な温度に。その反面、スキマ風でものすごく寒い冬には、床暖房と暖炉を採用したい。茅葺き民家は、じわじわと熱が伝わる輻射熱と相性がよく、体を芯から温めてくれる。

Thatched roof homes do not require air conditioning in the summer. During the day, it releases the heat from the sun so that the temperature will be cool and comfortable at night. But underfloor heating and a fireplace would be great to have during the cold winter months when cold drafts come into the home. Thatched roof homes are compatible with radiant heat that gradually warms the space and one’s body from the core.

ツルツルよりもデコボコがいい

Better bumpy than silky and smooth

築700年の茅葺き民家は、ちょうな削りの木の床だった。日本で最も古い大工道具「ちょうな」で、ウロコのように削られた床から伝わる足裏の感覚が心地よかった。家全体を冷やしてくれる効果がある土間も、現代の家に生かしたい知恵。

The 700-year-old thatched roof home had chiseled wooden floors. The chisel called “chona” is the oldest carpenter tool in Japan and the scale-like patterns it carved on the floor felt soothing under our feet. The dirt floor that helps cool down the entire home is a piece of wisdom that could be incorporated in the modern home.

呼吸する壁、直せる壁

Breathing walls, fixable walls

温度や湿度を調整してくれる土壁は、アレルギーやシックハウスの心配もない「呼吸する壁」。今ではモダンな左官仕上げのできる職人が増えてきているし、メンテナンスのたびに仕上げを変える楽しみもある。もうひとつ、内壁に使ってみたい素材は和紙。障子としてではなく、クロスの代わりに壁紙として。土壁と同じく呼吸する素材で、少しずつ直しながら良化させていくことができる。

Earthen walls that adjust temperature and humidity are “breathing walls” with zero worry of triggering sick house syndromes. Nowadays, there are more craftsmen offering modern finishes and one can enjoy changing the look of a given wall with every round of maintenance. Another potential material for home interior is Japanese paper, not for paper screens but as a replacement to wallpaper. Japanese paper, like earthen walls, is breathable, and its beauty also grows with repeated maintenance.

ローエネルギーな扉づかい

Low-energy doors

日本家屋は部屋を仕切る扉が引き戸になっていて、簡単に取り外しができる。夏には通気性のよい竹の格子戸、冬には保温性のある障子戸と、季節によって入れ替えたら気分も変わるしローエネルギー。

Rooms inside Japanese homes are divided by sliding doors that can be easily removed. in summer, bamboo lattice doors let breezes in while in winter, paper screen doors keep the heat in. Changing the doors by season helps change the mood with minimum energy.